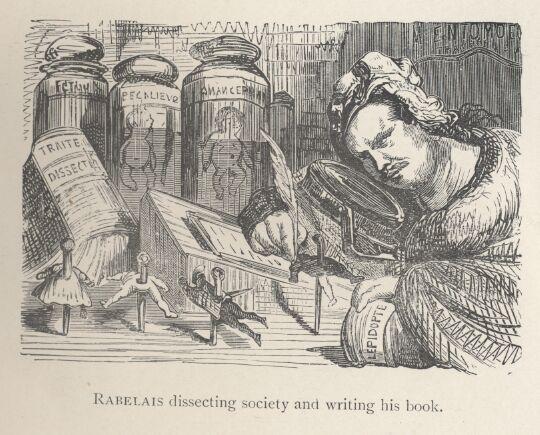

Get A Rise Out Of Rabelaisian Joke: In the 16th century, François Rabelais penned The Life of Gargantua and Pantagruel. It’s a lighthearted story of two giants, Gargantua and Pantagruel, and their exploits. From 1532 to 1552, Rabelais’ hilarious Masterpiece follows Gargantua and Pantagruel. “Gargantuan” and “Rabelaisian” are now synonymous with earthy humor, delectable food and drink, and sensual delights.

The censors at the Sorbonne rejected this collection of exaggerated stories. The stories defend ambitious and innovative ideas beneath their loud, frequently scatological wit. Rabelais uses ribald humor to discuss education, politics, and philosophy. His parodies of historical authors and Contemporaries satirize history, literature, religion, and society by exposing human folly. This version was translated by Sir Thomas Urquhart and Pierre le Motteux. Rabelais’ prose is described as “carnivalesque” in a new meta text. The notion of this work will be put to the test. Rabelais and His World by Mikhail Bakhtin inspired this concept (1965).

Unlike most other versions, Bakhtin analyses the new metatext utilizing historical, ideological, structural, and semiotic approaches. This is accomplished by referring to the text’s “carnivalesque spirit.” Bakhtin is referring to the 16th-century pre-Lenten festivities. He doesn’t mention carnivals from the Middle Ages or the Renaissance. The carnivalesque spirit of Bakhtin may be seen in 16th-century marketplace slang, student farces, charivaris, and other public amusements and celebrations. Rabelais’ few sections on Carnival, chapters 29 to 42 of his Fourth Book, are not evaluated by Bakhtin.

Rabelais and His World (Moscow, 1965; Cambridge)

by Mikhail Bakhtin, delves into the “carnivalesque spirit” (see 8–12). To distinguish the broad and narrow connotations of this Euro-American festival, I use caps and small typefaces in this book. The Roman Catholic season before Ash Wednesday, which can run anywhere from one or two days to six or eight weeks, is known as Carnival with a capital “C.” Carnival, spelled with a lowercase “c,” refers to a broader category of festivities marked by dazzling spectacle and inventiveness. In English and American contexts, such a spectacle has been commercialized and refers to a year-round venue with sideshows and exhilarating rides.

Outside of England, both Protestant and Catholic areas have broad and limited views. With the exception of New Orleans, Anglo-American towns have lost the restrictive classification. Bakhtin’s term “carnivalesque spirit” is a departure from the narrow definition; it has nothing to do with the carnival as spectacle and fantasy, and it has nothing to do with pre-Lenten alone. The “carnivalesque mood” is political in nature, mocking serious, “official” thinking and behavior. I used tiny fonts to show the broad meaning of “carnivalesque” and “carnivalesque spirit,” as did Bakhtin’s translators while cautioning readers not to mix Bakhtin’s broad meaning with Anglo-American use. The carnivalesque tone of Rabelais’ writings explains how and why they have become classics.

How did Rabelais come up with a carnivalesque language and adapt it to the world of bookselling?

Rabelais’ writing skills were influenced by the distinctive book creation and consuming practices of his day. In France and the West, the written book was less than 100 years old when his first volumes were published in 1532. Its components, shape, privileges, limits, and connection to political, economic, and ideological issues were all hazy. The supposedly carnivalesque work of Rabelais links to the new horizon afforded by the print revolution, which has taken a new turn with the computer.

Rabelais’ Carnival isn’t just for sake of Critical Analysis

Its four parts are self-contained and may appear to be separate as the reader reads. Rabelais’ first two books are published in Urquhart’s 1653 edition. The ‘M.’ initialed footnotes are from the Maitland Club edition (1838). Urquhart’s translation of Book III was released posthumously in 1693 in conjunction with a new edition of Books I and II edited by Motteux. Motteux translated Books IV and V in 1708. From Ozell’s 1738 manuscript, certain passages removed by Motteux have been restored.

If Rabelais hadn’t written it, no one would have considered producing his strange and marvelous romance. It’s a mash-up of madness and gravity, folly and reason, childishness and grandeur, the ordinary and the extraordinary, popular verve and polished humanism, mother-wit and learning, baseness and nobility, individuals and broad generalization, the comic and the serious, the impossible and the familiar. He is one of the best, and his peers are rare. He has a lot of life and thinking, good sense, and authoritative assurance. You can criticize him or praise him, but you can’t ignore him. He’s a Rough guy. Rabelais’ name will always be remembered, no matter how fastidious you are.

With each reading, we may learn more about, like, and admire his work. We can study it after we’ve enjoyed it to gain a better understanding. He won’t be able to understand his own life in the same way. Despite all of the successful efforts to shed light on it, such as the discovery of a new document or a long-forgotten book, the addition of a fact, or the pinpointing of a date, it remains riddled with doubts and holes. There’s also more to cut than to add because it’s bloated with tiresome stories and stupid anecdotes.

The furious attacks of a monk of Fontevrault, Gabriel de Puy-Herbault, who seems to have drawn his conclusions about the author from the book, and, more specifically, in Ronsard’s regrettable satirical epitaph, piqued that the Guises had only given him a pavilion in the Forest of Meudon, whereas the presbytery was close to the Since then, folklore has travestied Rabelais, making

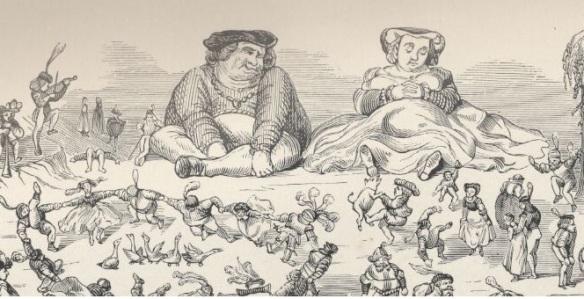

His physical look has Shifted

He had a full moon face, an incorrigible toper’s nose, and large, sandpaper lips that were almost always apart and laughing. His pals and he were taken aback by the photograph. I’ve seen a lot of portraits of Rabelais. They’re all from the 17th century, and the majority of them are amusing and popular. Only one portrait of him, the one in the Chronologie collee or coupee, is considered authentic. This double moniker refers to a large sheet divided into little squares by lines and cross lines and containing approximately 100 renowned Frenchmen.

This sheet was pasted on pasteboard and cut into pieces so that the individual portraits may be sold. The majority of the portraits portray well-known personalities who can be authenticated. These were carefully chosen and obtained from legitimate sources; sculptures, busts, medals, and even stained glass for the most illustrious, and earlier engravings for the others. The most expensive are those without copies, who have individual features, hair, beards, and clothes. They’re all unique. There has been no tampering or forgery. Each one has its own individuality. Around the end of the 16th century, Leonard Gaultier published this etching in the style of his master, Thomas de Leu.

These drawings had to be the originals of his portraits, and they may be just as legitimate and trustworthy as the others whose accuracy we can confirm. Rabelais isn’t the same as Roger Bontemps. His cheeks are thin and weathered, and his features are powerful, viciously cut, and wrinkled. His beard is short and sparse, and his beard is short and sparse. His demeanor is severe and unpleasant, and he wears the square headgear worn by doctors and clerks. Only this portrait is worth paying attention to.