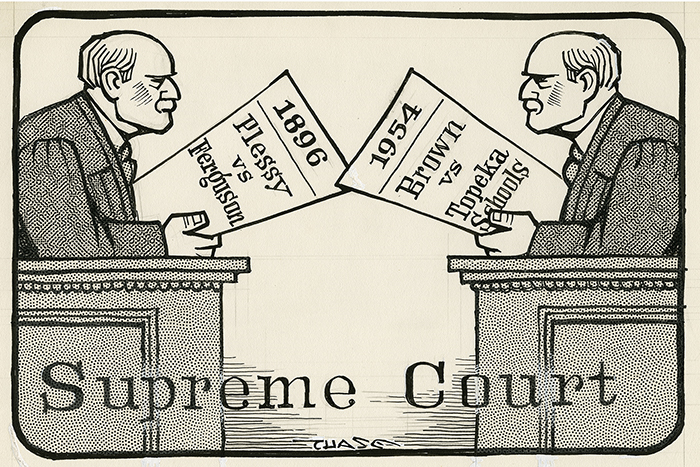

Plessy Vs Ferguson Brown Vs Board Of Education: Along with Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954), it is one of Louisiana’s most well-known court cases in the annals of American civil rights. Plessy v. Ferguson, ruled by the US Supreme Court on May 18, 1896, established “separate but equal” racial segregation as the law of the land for the following nearly six decades. It is one of three pivotal cases in American civil rights history.

https://twitter.com/retronewsnow/status/1262105738408718336

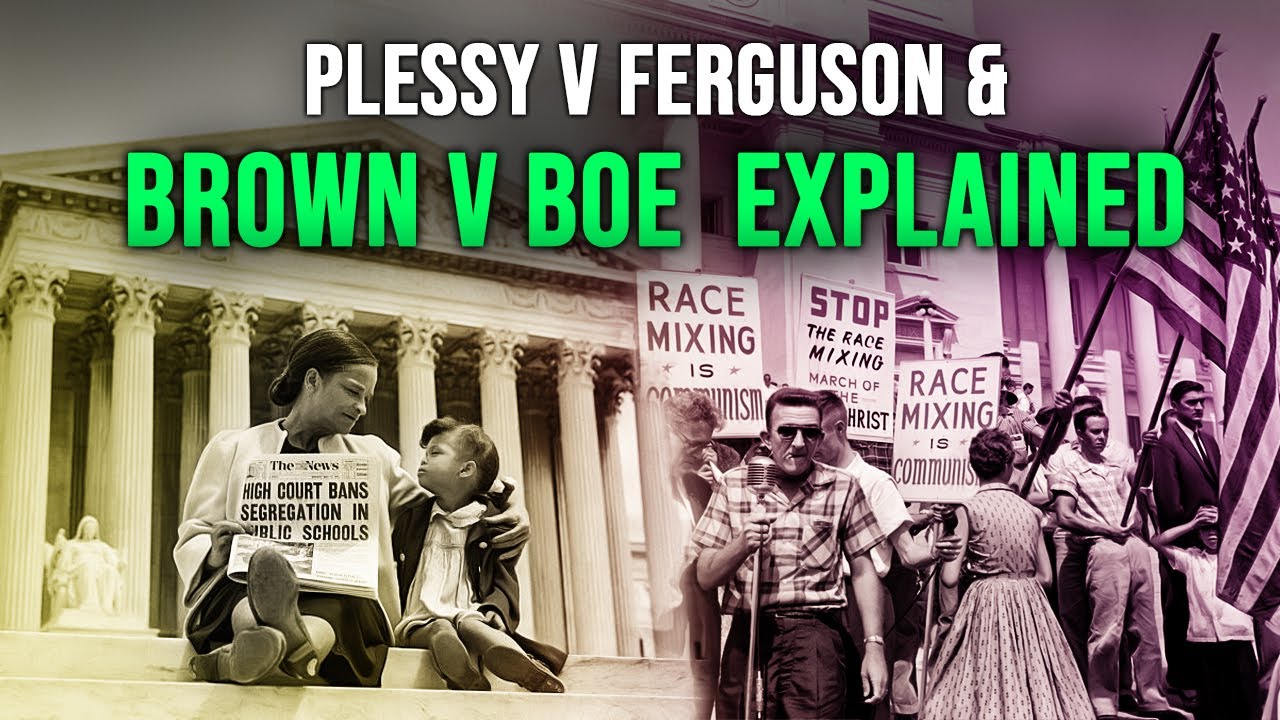

Homer Plessy, a native of New Orleans, was detained in 1892 for boarding a railway compartment reserved for white passengers in an effort to determine if Louisiana’s segregated trains were legal. Plessy v. Ferguson is one of the most significant cases in the history of American civil rights, along with Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954). All Jim Crow laws that considered African Americans to be second-class citizens were made legitimate as a result of the Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. The civil disobedience strategies used by the civil rights movements of the 20th century had their roots in this case.

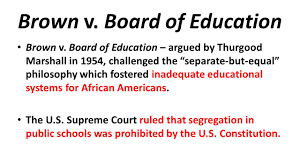

A prime example of civil rights law in action is the Brown v. Board of Education case

The way white people handled black people felt unfair. Their dissatisfaction led to Plessy v. Ferguson and the Supreme Court’s judgment in Brown v. Board, which reversed Plessy. This chain of occurrences was intended to repair the harm from 1896. Segregation and prejudice were fought against during the Civil Rights Movement and Brown v. Board of Education. It fosters a sense of inferiority in the community and can have long-lasting consequences on people’s hearts and minds when persons of the same age and qualifications are treated differently because of their race.

This is How it Began

Homer Adolph Plessy, the plaintiff, and judge John Howard Ferguson, who decided against him in 1892, both rose to fame as a result of the case. When Plessy was born Homère Patris Plessy on St. Patrick’s Day 1863, his parents Adolphe Plessy and Rosalie Debergue were listed as free persons of color who were both inhabitants of New Orleans and born before the Civil War. John Ferguson, a Massachusetts native-born in 1838, relocated to New Orleans following the American Civil War, where he established a legal practice in the Uptown neighborhood. On July 5, 1892, he took the oath of office as Section A Judge of the Orleans Parish Criminal Court.

The two men met one another around three months after Ferguson was appointed to the bench. The legal separation of races that had started to erode after the Civil War was attempted to be re-established in the lawsuit that brought them together. The Thirteenth (1865), Fourteenth (1868), and Fifteenth Amendments all accomplished emancipating the enslaved, establishing equal citizenship rights, and outlawing racial segregation (1870). The trend started to turn around in the late nineteenth century after the Compromise of 1877 destroyed the post-Civil War Reconstruction Administration.

The Louisiana legislature passed the Separate Car Act in 1890, which required segregation for white and black passengers riding in the same railroad cars. As a response, citizens of New Orleans established the Comité des Citoyens, or Citizens’ Committee for the Annulment of Act No. 111, in 1891. The majority of the Comité’s members were wealthy black Creole Republicans from New Orleans. (eltiempolatino.com To challenge the constitutionality of legislation that restricted the movement of individuals of different races on railroads, they raised money, organized protests, and hired attorneys.

It resembles the legal case of Plessy v. Ferguson

On October 13, 1892, Homer Adolph Plessy appeared before Judge Ferguson in Case No. 19117, Homer Adolph Plessy v. The State of Louisiana, and entered a not guilty plea to charges of violating the Separate Car Act. Plessy’s local attorney James C. Walker claimed on October 28 that the Separate Car Act was unconstitutional, but Judge Ferguson ruled against him on November 18. A judge found that no one could claim that Plessy was not treated equally with the white passengers. He was thus “simply denied the freedom to behave as he wished and to commit a crime without fear of prosecution,” according to the court.

Daniel Desdunes, a member of the Creole Onward Brass Band, offered to oppose the Separate Car Act on February 24, 1892, by purchasing a first-class ticket on the Louisiana and Nashville Railroad from New Orleans to Montgomery, Alabama, under the direction of the Comité. On the presumption that prohibiting him from doing so would violate the Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution, the choice to move to another state was made. On May 25, the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled that interstate travelers were not covered by the Separate Car Act, rendering the test pointless.

Plessy offered to be the next protester to maintain order. At the age of 32, he arrived at the Press Street train yards, which were adjacent to the Mississippi River, on June 7, 1892. He bought a first-class ticket on the East Louisiana train and sat in the first-class coach to Covington. When the train’s conductor told investigator Christopher C. Cain that a person of color was in the “whites-only” car, Plessy was detained for violating the Separate Section Act.

On January 11, 1897, Plessy returned to the Criminal Court in New Orleans, where she entered a guilty plea and paid a $25 fine. He received a one-year prison term. Even after the Supreme Court’s ruling, Comité des Citoyens persisted in claiming that segregation was unfair and unconstitutional. However, the case established a precedent. Because they believed that the federal government would defer to the states on racial issues, Louisiana and other southern states passed new segregation laws. Up until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the idea of “separate but equal” was universally accepted.

A unanimous ruling by the United States Supreme Court

Plessy hired Albion Winegar Tourgée to represent him in Case No. 210, Plessy v. Ferguson, before the US Supreme Court on April 18, 1896. Segregation, in Tourgée’s opinion, has the main impact of “perpetuating the stigma of color to make the curse perpetual.” On May 18, the Louisiana appeals court’s decision was upheld by a seven-to-one majority. Justice Henry B. Brown, speaking for the majority in the Supreme Court case, argued that the forced segregation of two races “stain colored race with a sign of inferiority.”

More than a century after the Plessy decision, the Crescent City Peace Alliance erected a historical memorial close to the spot where Plessy was detained in New Orleans. Members of the Plessy and Ferguson families attended a tribute on February 12, 2009, at the junction of Press and Royal Streets in New Orleans, Louisiana. The Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1966, in my opinion, were not enacted until after the Supreme Court’s ban on racial discrimination in Brown v. Board of Education was fully realized.

The Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of racial equality had not received much attention from judges or lawmakers until lately. In the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, separate but equal facilities were found to be legal. Many people were astonished by the Supreme Court’s decision to reverse earlier rulings on equal access to public facilities, which sparked a great deal of controversy. When the Supreme Court determined in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated schools were unfair, segregation barriers started to fall in the 1950s.