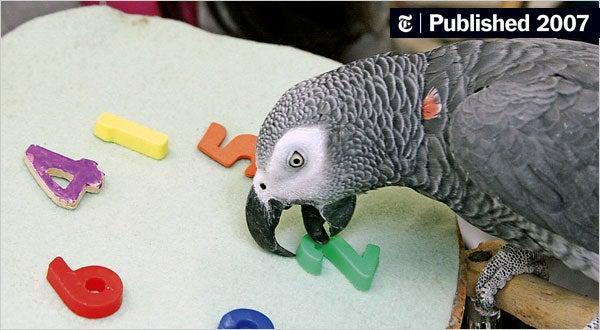

Alex The Talking Parrot Answer Key: Alex, a talking African grey parrot, was a fascinating case of avian vocal learning. Alex was “able to participate in some sorts of inter-species communication,” according to Dr. Pepperberg’s account. Alex was capable of far more than just imitating human speech patterns. Alex was taught to recognize specific objects by name, such as “key” and “paper.”

In order to categorize items by color and shape, it was also taught to call certain colors such as “green” and “blue,” as well as specific shapes with labels such as “three-corner” (easier to remember than triangle). It also learned to recognize amounts of up to five things, as well as the functional meaning of the word “no” and phrases like “come here” and “want to go.” It had been taught a functional repertoire of roughly 40 vocalizations after five years. When an object was held out in front of the bird, it correctly identified it eight times out of ten.

The deletion of the color or shape adjectives, or the poor pronunciation of the color adjectives, were his most common faults. When the trainer, for example, held up a green key and asked, “What is this?” Only 69 percent of the time did Alex respond with “green key.” If his response was mere “key,” as it frequently was, the trainer then asked, “What color key?” “.. The bird frequently got it right the second time, increasing its score from 69 to 94 percent. The bird could not identify unknown objects of recognizable colors when presented with them at random, yet it always got the color right.

Alex’s Vocabulary is Extensive

Alex was told “no” every time he misidentified an object. He began to use the word to his trainer after around 18 months of training when he appeared to not want to be handled. When trainers refused to relinquish an item requested by the parrot, they began to employ the word “no.” Alex would soon utter the word “no.” He would say “no” while refusing to identify a given object. “No” was also used to reject unreasonably little morsels of food, as well as toys that appeared to be too worn to be interesting.

The refusal to identify or relinquish is sometimes followed by the trainer turning his head aside. Alex spontaneously yet meaningfully utilized words that he had picked up in addition to the terms with which he had been trained. He “requested” food items or goods by pronouncing their names, prefaced by “desire,” despite not having been trained to make labels for the various foods. Alex would say “want cork” whenever a trainer took a very popular object, such as a cork, from a drawer and Alex saw it. He also requested objects that were not visible.

Language and Alex

Alex’s ability to invent simple word combinations, despite his limitations, was maybe the most striking feat of all. The bird was given a green clothes peg after being trained to recognize some objects as “green” and a clothes peg as the object “peg wood” (but never as a green one). “Green wood, peg wood,” he said. He should have stated “green peg wood,” but he was connecting words from his lexicon. On his first-ever presentation, he identified “blue peg wood,” “green cork,” and “blue hide.” By segmenting phrases and recombining the pieces in this way, you can start to meet one of the most important criteria for defining authentic language.

Alex The Talking Parrot Answer Key

Alex was born on May 6, 1976, and died on September 6, 2007, was a grey parrot who was the subject of a thirty-year study by animal psychologist Irene Pepperberg, which began at the University of Arizona and continued at Harvard and Brandeis Universities. Pepperberg bought Alex from a pet store when he was around a year old. Pepperberg describes her special bond with Alex in her book “Alex & Me,” and how Alex helped her understand animal minds. Alex stood for “avian language experiment” or “avian learning experiment,” respectively. He was likened to Albert Einstein because, at the age of two, he was answering questions meant for six-year-olds accurately.

Prior to Pepperberg’s work with Alex, it was widely assumed in the scientific community that a large primate brain was required to handle complex language and understanding problems; birds were not thought to be intelligent because their only means of communication was mimicking and repeating sounds to communicate with one another. Alex’s achievements, on the other hand, confirmed the theory that birds can reason and utilize language creatively on a fundamental level. Other scientists had failed to facilitate two-way communication with parrots, so Pepperberg used this strategy to assist him to succeed with Alex.

Alex’s intelligence, according to Pepperberg, was comparable to that of dolphins and giant apes. She also stated that Alex had the IQ of a five-year-old human in some ways and had not yet realized his full potential when he died. At the time of his death, she believed he had the emotional level of a two-year-old human. While working as a researcher at Purdue University, animal psychologist Irene Pepperberg purchased Alex from a pet store. Alex’s wings may have been clipped when he was young, preventing him from learning to fly, according to her.

Training

Alex was taught using a model/rival technique, in which the pupil (Alex) observes the interactions between the trainers. One of the trainers acts as a role model for the desired student behavior and is viewed by the student as a competitor for the attention of the other trainer. The trainer and model/rival switch roles so the learner may observe how engaging the process is. When Pepperberg and an assistant were conversing and made mistakes, Alex would correct them, according to Pepperberg.

Accomplishments

Instead of claiming that Alex could speak, Pepperberg stated that he communicated using a two-way code. “Alex” was able to recognize 50 different items and quantities up to six in 1999, Pepperberg reported. “He was capable of distinguishing 7 colors, 5 forms, and the notions of bigger, smaller, the same, and the different,” Pepperberg added. Piaget’s Substage 6 object permanence tests were progressively challenging for Alex. When confronted with a nonexistent object or one that differed from what he had been told was hidden during the testing, Alex reacted with astonishment and fury.

Criticisms

Some scholars are suspicious of Pepperberg’s conclusions, claiming that Alex’s communications represent operant training despite the lack of data or peer-reviewed publications pertaining to Alex’s data. A chimp named Nim Chimpsky was supposed to be using English, but whether he simply imitated his trainer is a point of contention. Herbert Terrace, who worked with Nim Chimpsky, believes Alex performed by rote rather than using language; He claims Alex’s responses are “a complex discriminating performance” without peer-reviewed publication, and that “there is an external stimulus that guides his response” in every situation.

Researchers who have worked with Alex and published data on him, on the other hand, claim that he was able to communicate with and perform for everyone engaged in the project, including complete strangers who recorded findings. Later in life, Alex took on the role of one of Pepperberg’s helpers by acting as a “model” and “rival” in the lab, assisting in the training of a fellow parrot. When Alex was alone, he would practice words.