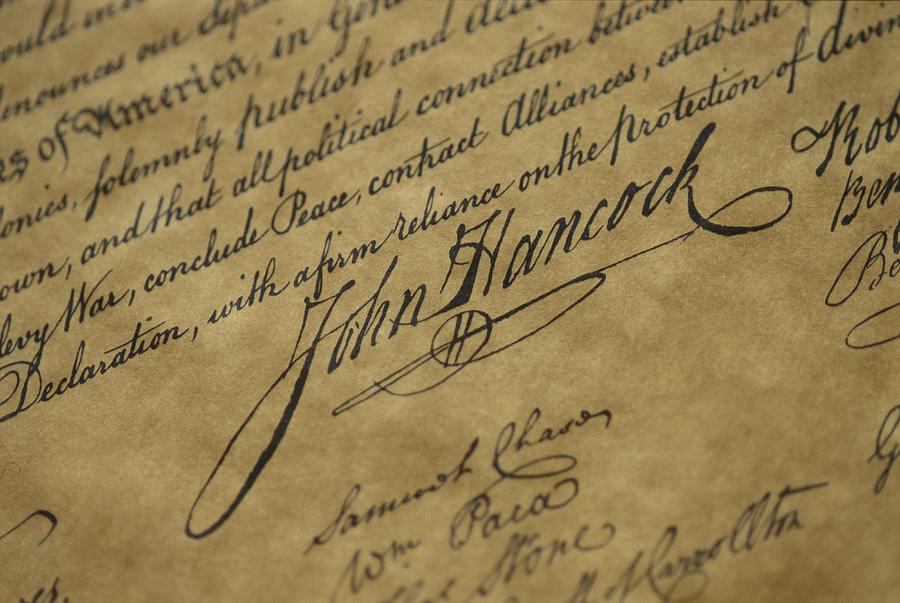

Add Your John Hancock: Is John Hancock correct in his assessment of his signature on the Declaration of Independence? Also! More Signing Tales! The parchment paper signed by the Second Continental Congress’s fifty-six members and dated July 4, 1776, is most commonly associated with the Declaration of Independence. Only a small percentage of Americans throughout the first two decades of the twentieth century shared this sentiment.

Those folks, for the most part, never had access to Congress’s papers, which were safely held in the embryonic national government’s archives. The Declaration of Independence was either a written text or a collection of spoken words to them. It was a piece of paper rather than parchment. In 1818 and 1819, the handwritten Declaration of Independence was first published in etched form, followed by a government-endorsed reprint in 1823. There were a few more copies made after that. Because the original was faded while copying, modern images, and keepsakes are based on the 1823 reproduction rather than the original.)

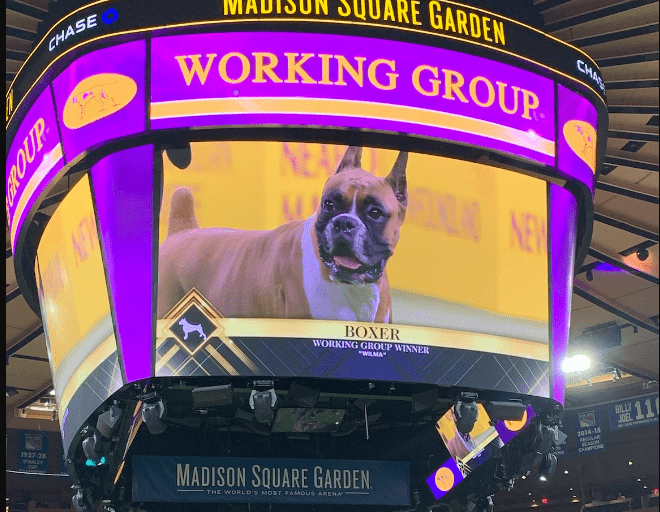

The Declaration of Independence became known as an eloquently signed handwritten declaration by the American people. Because of this, those autographs, particularly John Hancock’s, became icons of American patriotism. Even though the signing did not begin until August 2 and was scheduled for July 4, the act of signing the paper became more significant than Congress’s actual votes to ratify independence and the Declaration’s contents. The fifty-six members of Congress who signed the Declaration of Independence have become more famous than any other members of Congress. The stories about how the names were etched into the paper enthralled the people.

However, with the Colonial Revival in the late 1800s

historians began to reject these claims. Authors sometimes insert a disclaimer that the narrative is most likely a legend when repeating one of these incidents. In this article, four such articles are analyzed with the purpose of judging how truthful and reliable they are. The results aren’t always predictable. One of the larger Virginians, Benjamin Harrison, joked about how long it would take each of them to be hanged in the first anecdote. According to the Course of Human Events blog, this is one of several “quotations from the signing for which we have no evidence. (www.christophechoo.com) ”

According to an essay in the Weekly Standard, if the story is accurate, it is most likely a fabrication. This story can be linked to one of the males in the room where the incident occurred. Dr. Benjamin Rush reported the event in a letter to fellow Signer John Adams dated July 20, 1811:

Do you recall the profound and terrible calm that engulfed the house when we were brought to the President’s table to sign our own death warrants?

The calm and gloom of the morning were abruptly disrupted when Col. Harrison of Virginia said to Mr. Gerry at the table, “I shall have a big advantage over you Mr. Gerry when we are all hung for what we are now doing.” I’ll be dead in a few minutes, but because of the lightness of your body, you’ll be dancing in the air for an hour or two before dying.” There was a short grin on everyone’s face after this speech before things reverted to their customary solemnity.

This was a private correspondence between friends before the handwritten Declaration became an icon. It was not created with the intention of delighting the general audience. Dr. James Thacher’s Military Journal originally published this narrative in 1823, which includes his actual battlefield notes as well as later recollections and other sources.

In a 1776 journal entry, Thacher wrote the Following:

On the day the proclamation was signed, this episode is said to have occurred. When it comes to the delegates from their various states, Mr. Gerry of Massachusetts and Mr. Harrison of Virginia are noticeably different in size. “When the hanging situation comes to be exhibited,” Mr. Harrison smirked as he told Mr. Gerry, “I shall have the edge over you due to my size.” After the serious transaction of signing the instrument a few times. My stay here is over, but you’ll be kicking and screaming for at least a half-hour after I go.”

The anecdote may have been given to Thacher by Rush, with whom Thacher interacted. The way he phrased Harrison’s remark, on the other hand, is significantly different from the way Rush phrased it for Adams. Harrison spoke “at the table,” according to Rush, whereas Thacher claims he spoke “a little time after the solemn event of signing the paper.” In any case, it’s the same story that’s being told over and over. John Adams, who was known to be critical of Revolutionary myth-making when he wasn’t doing it himself, accepted both Rush and Thacher’s stories.

He did not protest the account in his reply letter to Rush, even though he loathed Harrison and began to consider Gerry as a political rival. In 1824, Adams read Thacher’s Journal of the American Revolutionary War to him, and he stated, “I have no hesitation in admitting, that it is the most natural, plain, and truthful narration of facts, that I have seen in any history of that period.”

What is your neighborhood’s “John Hancock”?

The following posts will serve as an introduction and stimulate your interest in individuals unfamiliar with history, historic resources, and historic preservation. To begin, I’d like you to think about what makes your community unique. Because it’s difficult to recognize such things, the Declaration of Independence is a good place to start. John Hancock, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, is depicted in this 18th-century oil painting.

What is the first thing that comes to Mind?

Most of us will recall John Hancock’s signature, which is prominently displayed beneath the main text. Because his signature is huge, forceful, and distinctive, it sticks out among the many others of his famous colleagues. “Signature elements” or “signatures” have come to be thought of as “signature features” for communities. A community’s signature, unlike John Hancock’s on the Declaration of Independence, is founded on its unique history, people, arts and architecture; natural resources; culture; commerce; agriculture; industry and institutions; and institutions. Because there are so many diverse components in each site, no two are ever the same.

On the other hand, a community’s signature elements can serve as a perpetual source of pride, inspiration, and creative energy. Community leaders can use these raw materials as building blocks in their efforts to revitalize their towns and attract investment by leveraging them to tell their stories and attract new residents and visitors. A community’s distinguishing characteristics can be used in a variety of ways. When it comes to examples, consider the following:

The ancient shipping crate of H.G. Hotchkiss

Lyons, New York, one of New York’s oldest towns, has relied on the Erie Canal and the H.G. Hotchkiss International Prize Medal Essential Oil Company, which produced peppermint and other essential oils, to revitalize its main street. All versions of this story about Hancock’s signature hinge on the fact that the Continental Congress never meant to send the parchment signed by Hancock to Great Britain. As previously stated, the paper was carefully kept by the American government’s archive. The Congress had already printed and sent copies of its Declaration to the United Kingdom and other countries, which had Hancock’s signature at the bottom.

Hancock’s signature was elaborate either for the benefit of his fellow delegates or for the sake of history. As a result, the narrative about John Hancock’s signature and King George’s spectacles is untrustworthy. Two of the three legends concerning the signing of the Constitution, according to that patriotic myth, which some authors are still repeating today, have a more solid foundation.