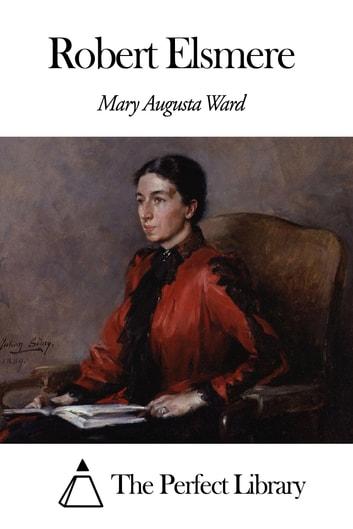

Robert Elsmere Author: By Mrs. Humphry Ward, Robert Elsmere is a novel published in 1888. [1] Over a million copies were swiftly sold, and Henry James expressed his enthusiasm for it. Robert Elsmere, first Published in 1888, was possibly the most popular book of the nineteenth century. Taking inspiration from her father’s religious turmoil, Ward depicts an Oxford clergyman who comes to doubt Anglican principles after seeing German rationalists.

Background

A clergyman at Oxford begins to doubt the Anglican Church’s doctrines after reading the writing of German rationalists like Schelling or David Strauss. It was inspired by the religious crises of her father Tom Arnold, Arthur Hugh Clough, and James Anthony Froude (especially as expressed in Froude’s novel The Nemesis of Faith). Elsmere, on the other hand, rejects both atheism and Roman Catholicism in favor of a “constructive liberalism” (a term used by Thomas Hill Green), emphasizing social engagement with the underprivileged and ignorant. Her uncle Matthew Arnold, Benjamin Jowett, and Mark Pattison were among the characters in Ward’s novel Robert Elsmere who were inspired to write it after hearing a sermon by John Wordsworth who argued that religious unrest like that in England during the nineteenth century leads to sin.

Ward decided to respond by creating a sympathetic, loosely fictionalized account of those involved in religious unrest today. William Ewart Gladstone famously panned the book for advocating the “dissociation of the moral judgment from a distinct system of religious formulae.” To put it another way, Oscar Wilde famously remarked in his article “The Decay of Lying” that Robert Elsmere was “merely Arnold’s Literature and Dogma with the literature left out.” However, Elsmere does not want to become an atheist and instead advocates for “constructive liberalism,” emphasizing the need for social work for the underprivileged.

Made the novel a best-seller

As a freeing tool for a liberated period, Robert Elsmere attracted the attention of intellectuals and agnostics as well as those of faith who viewed it as a step in the advancement of apostasy or heathenism. Many best-sellers have been reprinted and unlicensed editions have sold as many copies as approved ones. Despite the fact that the book had been out of publication for twenty-five years, a scholarly version of it was published in 2013 and included excerpts from Gladstone’s critique of it.

Dramatization: It was decided right once that the play would be staged at New York City’s Broadway’s Madison Square Theatre. Sherlock Holmes actor/playwright William Gillette was given the duty of playing the detective. He read the work to ascertain, as he put it, “whether or not there existed sufficient dramatic material in the book for stage purposes. On discovering that, with a little adjustment, a successful play might be made out of the motive discovered in it, I informed those managers and wrote at length to the author requesting her permission and offered generous royalty.” There would be no theological discussion whatsoever in the presentation of the material, he told Mrs. Ward. On the other hand, “because those who see the theatre as a mere place of entertainment and buffoonery are the same hopelessly limited and bigoted people who still hold it to be an agency of the devil.”

Setting: Much of the novel is set in and around Longsleddale in the Lake District, nicknamed by Ward ‘Long Whindale’. As a result, the eerie ‘High Fell’ described in the novel is actually High Street in real life.

In addition, he had reassured her that if she agreed to something only to change her mind, her wishes would be fully respected. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was pirated and sold overseas without the author’s permission, and the story was reworked and staged in America, with many of the adaptations based on the prejudice of the actors, which harmed the original novel “If, after receiving it, Mrs. Ward still refuses to give us her approval, the piece will not be completed under our supervision.

Cheap and Reckless Versions

A number of cheap and reckless versions will be presented to the audience instead, hastily brought to the stage by careless parties, just as hundreds of thousands of cheap and ill-printed copies of the book were released and sold. The virtuous people who have participated in literary theft by purchasing and reading these unlicensed and unpaid for publications will then give us a surge of outraged indignation against the theatre.” [18]

Gillette cited this as still another issue: “The literary trade between the United Kingdom and the United States, at least in the realm of theatrical production, is closer to war than peace. Anglo-Saxons take our work and perform it as they see fit, with little regard for attribution or seeking permission first. Retaliation of any kind, if one is inclined to it, is certainly acceptable. Honestly, I’m not a fan.”

In a report by Gillette, “My plans to stage a play based on Robert Elsmere were dashed when Mrs. Ward refused to grant me permission to do so in the end. Other people and organizations completed, rehearsed, and staged the play.” As soon as preparations could be made, producer Charles Frohman said that what Gillette had declined to do would be presented in a play in this city, “and the work, which has already been booked around the country, will be presented.”

According to the Boston Globe

Casting for the play had been finalized and rehearsals had begun by March 18, according to a statement. Playwrights “had done their work neatly” when the play launched at the Hollis Street Theatre in Boston on April 8, according to the Boston Globe.

On April 29, 1889, David Belasco staged Robert Elsmere in New York’s Union Square Theatre. Due to a lack of interest, it was only broadcast for two nights before being canceled. The play’s primary flaw was that it dealt with subject matter that was too heavy for most theatergoers to handle. When it came to social or economic or psychological considerations, most middle-class men of the late nineteenth century didn’t see life that way,” Catherine Marks said.

“Dramatic conflict was viewed by them as a fight between the individual and either external forces or his own conscience. No one was in any question as to what was “right.” Henrik Ibsen of Denmark and George Bernard Shaw of England began to draw attention in the 1890s when cracks began to develop in the European theatre. However, social issues and subjective depth probing drew only a small audience in the United States.”